Now, this is the way it is. Plain and Simple. I don’t like for anyone to take my picture.

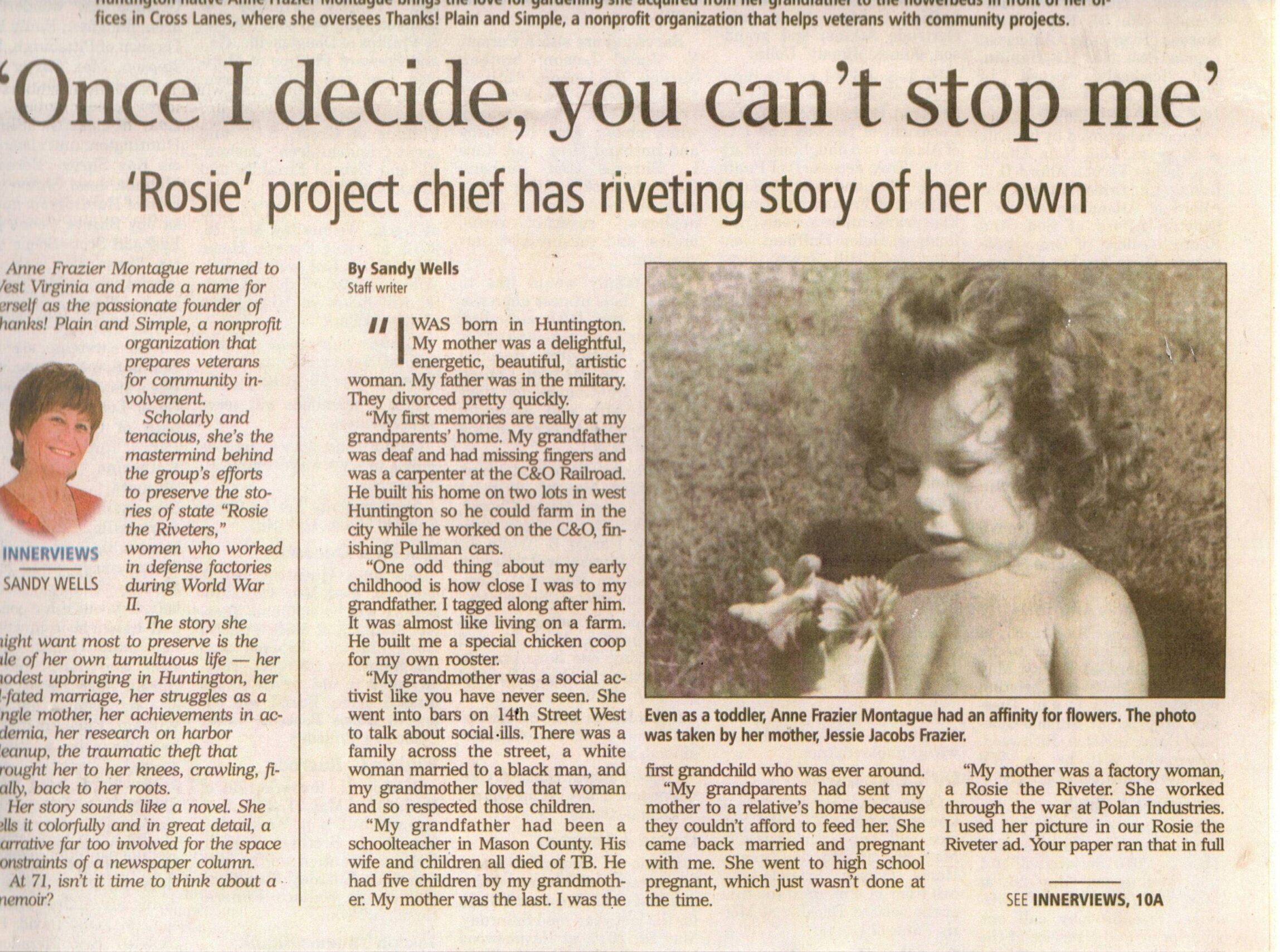

The only picture of me I like was taken by my Mother when I was two years old.

Mother captured the real me in one instant on that summer day. I was two years old.

It’s a black-and-white photo. I’m pulling petals off a flower—a big dandelion, I think. It’s clear that I love learning about the flower; my slanted eyes are focused, I’m not self-conscious, about my bare chest, a hair clasp holds my dark, curly hair away from my face, and I’m in the moment. And, maybe . . . just maybe, I have a slight smile of accomplishment.

That was 1941. A whooooole lot has happened to me and the world the 82 years that day in Ritter Park in Huntington, WV. But one thing that has not changed is I don’t like to have my picture made.

Throughout my life, so many people have insisted they let me take their picture that I finally made a promise to myself that someday I’d learn to like to be photographed. Someday.

In high school, I was elected homecoming queen by my classmates and the football team at Huntington East High School. When I heard the news, I went to our Dean of Girls, Mrs. Graham, and told her I was going to turn it down—it should go to the runner-up, Ruth Ellen Rogers. I said that my sister, Leah, was disfigured from cancer surgery—scars on her neck, a drooping eye, and she wasn’t in school—so it would be pretentious of me to be a queen of any sort. She told me to ask Leah if it would bother her. I did. Leah insisted that I accept it. She was proud of me, her older sister. She wanted every chance for me.

So, I gave in, but waving at people from a convertible that was driven around the football field and up city streets with my quiet, handsome high school escort beside me only increased my disgust at having my photo taken.

However, something happened a dozen years later. I had children, and like Mother, I took photos of them and had someone take my picture with them. How I treasure those photos – me with my children decorating birthday cakes, opening Christmas presents, reading them stories.

I started to realize that I was delighted to be doing something with others but not being featured myself. I’d like the focus to be on us, not on me.

Then, in my forties, I found myself alone in new places: Tokyo for a year and Boston for years. I went back to not wanting anyone to take my picture. Then I realized that if I carried a camera, people did not want to take my picture, because I was taking their picture. Somewhere I have pictures of flowers, the sunrise, street musicians, and the schooner called the Adventure when it returned to its home on the North Shore of Massachusetts after decades in Maine. I’ll find those photos someday.

But even when I knew interesting and even famous people—B.F. Skinner, my wonderful African friend Celine Nkenfu, who got her Ph.D. in biogenetics under a Nobel Prize winner, and many other people who are precious to my life—I would not let anyone take a picture of me with them. Then, I began to realize that this was a shortcoming because people who have been precious to me at different times of my life don’t know other people I value, and I can’t even show them a photo.

Then, in my early 60s, I returned to my home state of West Virginia for my 45th class reunion. I intended to stay only a short time, but I realized that I should stay to honor Mother, who was not properly appreciated. I started finding American women who, like Mother, worked on the home front during World War II – in factories, farms, shipyards, and in government offices.

I was totally in my element with these women from the first interview. They were at least 20 years older than me when I started. Their fascinating stories inspired me and others to do something to teach the world what these women really stood for.

As I worked with them to design and build a park, to create music and art that raised awareness of who they were, to put up bluebird nest boxes to represent hope, and on many more projects, I saw that people will pull together if they have the right reason, good guidance, and feel they are part of something bigger. I didn’t stop to raise big money for the work, but somehow, with the help of many people, Rosies were being honored for pulling together. But, I still didn’t like having my picture taken.

Now, to the day that changed me.

It was June 2nd, 2015. A beautiful day at Arlington Cemetery. The king and queen of the Netherlands had heard the European media interviews of three Rosies and me when we were hosted by the Freedom Museum in Nijmegen. So, the royal couple told the US President and the Netherlands Embassy in DC that they wanted to meet four Rosies at Arlington Cemetery. I had only three weeks to find Rosies who could go, get them there despite mobility problems, and have them ready to tell the royal couple meaningfully, but briefly, who each Rosie was.

So, somehow, after being elegantly dined in a beautiful hotel with a panoramic view of Washington the night before, I found myself with four Rosies in the foyer of Arlington Cemetery awaiting a personal introduction to the king and queen.

Now, this foyer is one special place. It wrapped us in dignity with its white-tan marble floors and walls, overhead circular lights, a strip of red carpet, a front door going to the tomb of the unknown soldier, and an interior door going to a room where the king and queen would emerge and greet each Rosie, one by one.

My pride in the Rosies was clearly shared by the Embassy staff. The royal couple’s frontman came out, got the stories of each Rosie and me, and disappeared.

Cameras – still and video – were everywhere. I was ready. This was the day I would be glad to have my picture made, and it would be with the royal couple after they met Rosies.

Then the king and queen appeared. Now, I thought I was ready for any tone they would bring to the moment, whether it be a stiff pretense or friendly chatter. But I was completely disarmed by the deep compassion that Queen Maxima and King A-W (will check to spell) showed when they looked at the Rosies. I was touched by their caring.

First, the royal couple greeted Mozelle Brown, one of the humblest people I’ve ever known, who riveted Corsair airplanes in Ohio and never had children. Her quiet manner set the pace.

Cameras flashed and rolled.

Then, they sent down the reception line to June Robbins, an extroverted Jewish woman who had dropped out of high school to draft ship parts in the Philadelphus Ship Yards, had been a world traveler, sometimes on a motorcycle, had been a certified clown, and had seven children. My pride grew as I saw they easily accepted June’s directness as deep sincerity.

Cameras flashed and rolled.

Then the royal couple greeted Anna Hess, a practical, ram-rod straight woman who had made truck tires in Ohio, had been a labor-union supporter while she worked as a seamstress making shirt collars for 35 years after the war, then had delivered Enterprise Rent-A-Cars on the east coast. Anna looked the couple in the eye, standing taller than the queen who wore spiked heels, and was as dignified, in her own way, as the king and queen.

Cameras flashed and rolled.

When the royal couple came to Ada England, she was so bent over from osteoporosis that I was not sure she could see the couple’s faces. All were touched and amazed that she had welded ships in Portland, Oregon during the war. As cameras flashed and rolled, I noticed that one of the small circular ceiling lights looked like a halo above Ada’s head, and I prayed that a photographer would capture it.

Then it was my turn. I started to repeat the description I’d given the frontman a short time earlier. I said, “I’m Anne Montague, director of a nonprofit organization that creates projects that should be done in America.” Our goal is to unify diverse people by showing how Rosies pulled together . . ..

Queen Maxima interrupted me. With undisguised kindness, she said, “But Anne, there’s no time!”

I burst out crying. Cameras dropped or turned away.

Through my tears, I said, “I know. I know! Time is running out1”

I don’t remember much after that, except that as I got on the bus with the Rosies, I babbled to some Dutchmen—something about how many Rosies took care of veterans injured in body and spirit after the war.

But I do remember a moment the next day when I made a resolution that I still hope to keep. I was alone riding an Amtrack train back to the West Virginia mountains. As I passed tree after tree, I realized that someday I must thank Queen Maxima for making me cry, because she was right – our time with our precious Rosies is coming to an end.

And I also resolved to let her know that the message that Rosies have given over 15 years of working with them is this: They want to be known for showing people that we can pull together to do quality work to preserve our freedom. And that need will never die.

Maybe I will even let somebody take my photo with her as we—two seemingly very different people—show the world that “we the people” not only can – but will – join across our differences to learn to pull together because we have the freedom to do.

I promise to try not to cry as our picture is taken. But if I do, it will be tears of joy because we are showing that people of all kinds will work together.

DUMP:

Pretty is as pretty does.

A photo is yet to be taken.

Good work is worth more than a million poses pictures.

The Queen and the Rosie’s Daughter